- Published on

Venezuela’s Oil Shock: Big Reserves, Small Moves in Markets

- Authors

Well, here we are. January 2026. My last blog post was in November 2024, which means I managed to completely ghost this space for over a year. No excuses, no dramatic explanations - just life getting in the way, as it tends to do. But I’m back now, and I’m planning to write regularly again: two to three posts a fortnight, maybe stretching to a month when things get busy.

2025 was absolutely wild - a year when politics lurched to the right across Europe, AI coding tools quietly transformed software development, markets digested another round of tariffs and rate cuts, ceasefires were negotiated, and fashion went through its biggest creative reshuffle in decades.

For this first post back, Venezuela feels like the right place to begin.

Table of contents

- Why Venezuela is back in focus

- A short history of a long crisis

- “300 billion barrels” and why quality matters

- Global markets

- A macro view

Why Venezuela is back in focus

Venezuela has lived in “crisis mode” for years, but early 2026 pushed it back into the centre of the news. A U.S. special‑forces operation in Caracas targeting President Nicolás Maduro has raised real questions about who runs the country and who controls its oil exports.

This is not just another round of sanctions. It mixes regime‑change risk, Washington’s direct involvement and the fate of huge oil reserves. For markets, the key question is not “is this the next global shock?” but “where, exactly, could this matter?”

A short history of a long crisis

Very short version of the last two decades:

Oil boom to bust

High oil prices in the 2000s funded big social and state spending while the rest of the economy stayed weak. The country became even more dependent on oil, with little buffer for bad times.As one think‑tank summary of Venezuela put it, petrostates are those where the government becomes deeply dependent on oil income, power is concentrated at the top, and other parts of the economy wither

Policy mistakes and sanctions

Price controls, expropriations and years of under‑investment hurt production. Sanctions later blocked access to finance and markets. The result was a collapse in output, hyperinflation and one of the deepest economic contractions outside of war.

Venezuela's political leadership Default and legal limbo

By 2017, Venezuela and state oil firm PDVSA had defaulted on tens of billions of dollars of debt. Estimates for total external obligations, including bonds and legal claims, run well above 100 billion USD, but the exact number is fuzzy.

Venezuela's main global exports Failed opening, then reversal

In 2023–24, there was a brief thaw with the U.S.: steps toward freer elections in exchange for limited sanctions relief on oil. When the electoral process again shut out key opposition figures and raised fraud claims, sanctions came back and relations soured.

That brings the story to today’s sharper turn: military action on top of sanctions and a regime that is still trying to hold on to power.

“300 billion barrels” and why quality matters

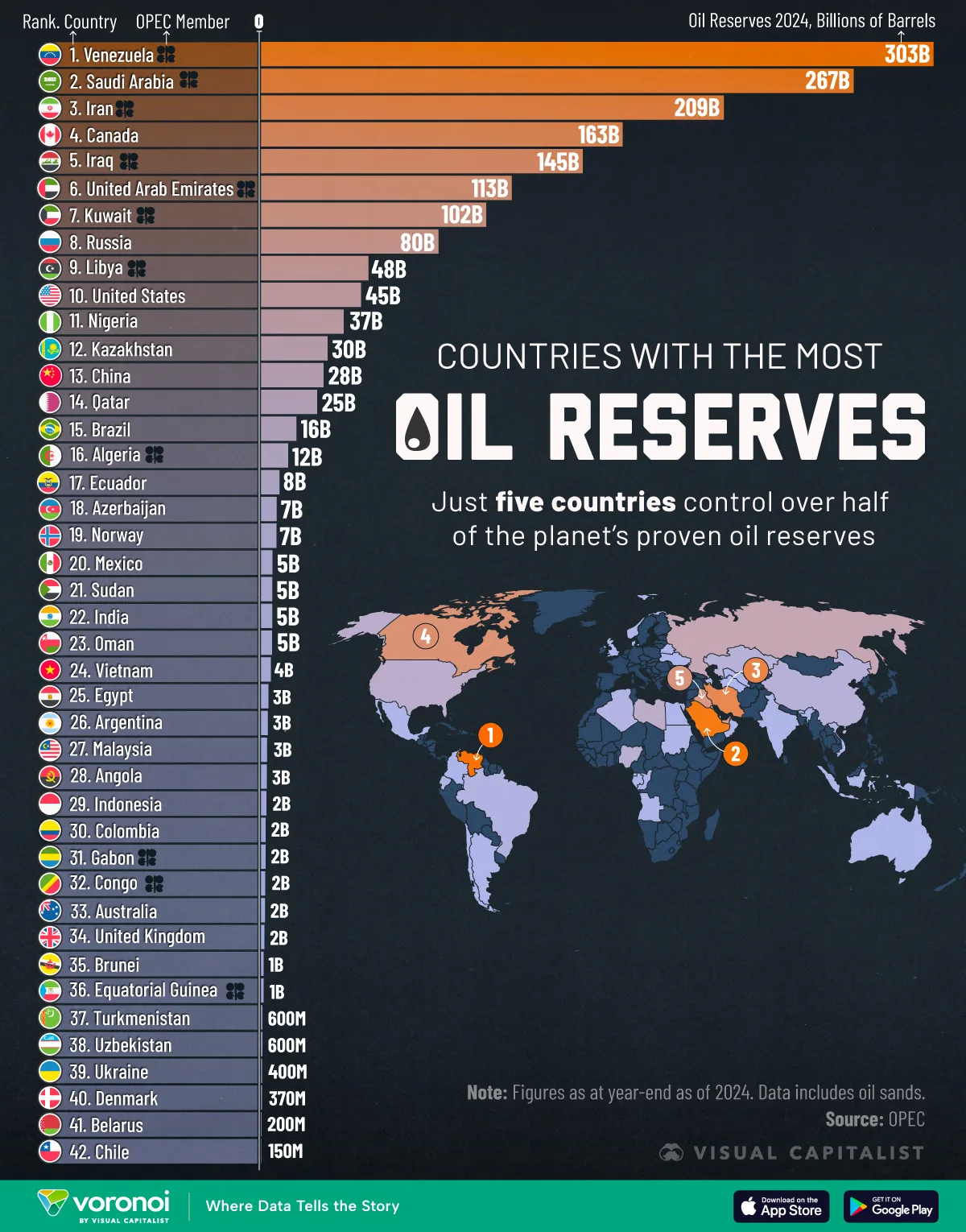

One headline keeps coming up: Venezuela has the world’s largest proven oil reserves, roughly 300–303 billion barrels, or about 17% of global reserves. On paper, that beats Saudi Arabia and Iran. But there are three big catches.

1. Heavy, “dirty” oil

Most of Venezuela’s reserves sit in the Orinoco Belt and are extra‑heavy or heavy crude. This oil is:

- Very thick (high viscosity) and often high in sulphur.

- Harder and more expensive to extract and move.

- Less valuable per barrel than lighter “sweet” grades unless refineries are built to handle it.

Analysts often describe it as “dirty” oil because it needs more energy, more processing and produces more emissions compared to light crude.

2. Weak infrastructure

On top of the oil quality problem, Venezuela has:

- Aging, damaged refineries and export terminals.

- Shortages of diluents (lighter hydrocarbons used to blend with the heavy crude).

- Limited power, maintenance and capital after years of under‑investment and sanctions.

Reports estimate that getting production back near early‑2000s levels could require over 100–180 billion USD in new investment spread over many years. That assumes a more stable political and legal environment than exists today.

3. Reserves vs. real output

So while the reserve figure is huge, current production is low, well under 1 million barrels per day in recent years. Output has fallen far from past peaks above 3 million barrels per day.

Global markets

Energy companies with old Venezuelan ties or heavy exposure to similar grades will feel the swings most.

1. Oil prices and energy stocks

Venezuela changes the story around oil more than the immediate numbers.

Near term

- Because sanctions and decay already held exports down, the latest shock does not remove a huge volume from global supply overnight.

- What it does add is risk premium: traders price in the chance of wider disruption or a messy transition. That can possibly mean a few extra dollars on Brent or WTI during tense weeks, even if physical flows barely move.

Medium term

There are two broad paths:- A gradual normalisation with clearer property rights and some political stability could unlock investment and lift Venezuelan output over several years, acting as a mild cap on long‑run prices.

- A prolonged conflict or split authority would leave reserves stranded, keep output depressed and add to the case for higher structural prices, especially for heavy crude needed by some refineries.

2. EM debt and credit

Venezuela is already in default, but price moves in its old bonds say a lot about how investors are thinking.

Distressed bonds as a political bet

Defaulted Venezuelan and PDVSA bonds have traded higher in recent years as markets priced in a small but rising chance of eventual regime change and restructuring. The latest events increase both the upside and the downside: a cleaner transition could mean better recovery values, while chaos could delay any deal for years.Spillover to neighbours

So far, there is only limited direct contagion to other emerging‑market sovereigns. A possible rise in the risk premium for countries where sanctions or regime shifts are part of the narrative. Here, Venezuela acts more as a reminder of political risk than as a direct shock to the whole EM universe.

3. Currencies and rates

The FX and rates angle is more modest but still worth watching:

- Oil exporters can see mild support if traders expect tighter supply and firmer prices, while importers may face a bit more inflation pressure and tougher rate‑cut choices.

- Classic “safe havens” like the U.S. dollar and high‑grade bonds can benefit at the margin during spikes in geopolitical tension, though the moves around Venezuela so far look smaller than during other big crises.

4. Legal claims and long timelines

If the country eventually moves to a recognised transition, there will be a long process of sorting out:

- Sovereign and PDVSA bonds in default.

- Arbitration awards and past expropriation claims.

- New contracts for oil investment and revenue sharing.

These are multi‑year stories more than short‑term trading events. They matter for specialised investors and for how future resource‑rich states think about contracts and sanctions.

Venezuela Crisis Sends Shockwaves Through Oil Markets

A macro view

This post is an attempt to make sense of how a political and humanitarian crisis in one country connects to oil prices, emerging‑market debt and risk appetite more broadly.

For most diversified portfolios, Venezuela is likely to show up as:

- Extra volatility in oil and related assets from time to time.

- Small shifts in risk appetite for EM credit and FX during sharper episodes.

- A longer‑term question about when, and under what conditions, those huge heavy‑oil reserves actually matter for global supply.

The story is still unfolding, and the range of outcomes is wide. But even in a noisy, headline‑driven situation, the old rule holds: size, timing and quality of supply matter more than big reserve numbers on a chart.